Wine History

Wine's Surprising Influence on the History of Calculus

The astronomer Johannes Kepler, best known for advancing our understanding of the cosmos with his laws of planetary motion, also aided the development of calculus, with a little help from wine.

Beyond the essential joy of drinking it, the most alluring of wine's qualities may be its connections to history. Showing up in records and archeological findings dating back thousands of years, and in descriptions of significant events, including the signing of the United States Constitution, it is captivatingly intertwined with the past.

After all, who wouldn't care to try a wine from a château that Thomas Jefferson visited and praised, such as First-Growth Bordeaux estate Château Haut-Brion? Renowned wine-importer Kermit Lynch even includes the (perhaps misquoted) saying from Jefferson on the back label of each wine in his portfolio: "Good wine is a necessity of life for me."

But in most instances, wine is relegated to the background, merely present as the primary historical events of the times unfolded, a beverage enjoyed while notable political, scientific, and artistic contributions were made. There have been, however, a few occasions when wine played a key role in defining history's trajectory.

Which brings us to Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), the famed astronomer who discovered the elliptical nature of celestial orbits and built on Nicolaus Copernicus's theories, culminating in his own three laws of planetary motion that are still relevant to this day.

Less well known is that Kepler also contributed to the development of the precursors to calculus, the field of mathematics that is fundamental to almost every branch of science—as well as engineering, finance, computer science, and medicine, among numerous other fields of study and practice. His initial work on this foundational discipline was later developed and formalized by Gottfried Leibniz and, most famously, Isaac Newton, who is often regarded as the true creator of calculus.

Yet it was no falling apple that spurred Kepler’s breakthrough, but rather a bit of vinous intervention.

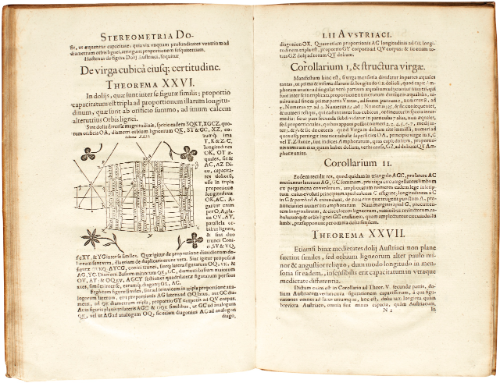

Kepler's Nova Stereometria Doliorum Vinariorum

In fact, it was wholly due to a wine delivery that Kepler was inspired to formulate and write his Nova Stereometria Doliorum Vinariorum, translated as "New Solid Geometry of Wine Barrels." Published in 1615, this work influenced the development of calculus later in the century, though Kepler is not often credited for it.

Statue of Johannes Kepler in Linz, Austria | Aldaron, CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The moment of inspiration occurred in Austria in the early 1600s, as Kepler was to be married to his second wife, Susanna Reuttinger. In need of wine for the wedding and for his new household, he placed an order with the local wine merchant. Upon arrival with the requested barrel of wine, the merchant inserted a marked rod into the hole in the side of the barrel, moving it until the end reached the edge of the base inside. Reading the number on the rod at the opening, the seller declared the volume and price of the wine delivered.

As a mathematician, a scientist, and a careful thinker, this baffled Kepler. He believed it to be a wildly inaccurate method of measurement, as not all wine barrels were of the same shape or dimensions. Seeking a better technique to precisely measure the volume, he advanced the concepts of so-called infinitesimal techniques, building on the work of Archimedes from almost two thousand years earlier.

Essentially, to calculate the volume of a complex body—such as a wine barrel—he posited that the vessel could be divided into smaller, theoretical shapes that were easier to evaluate, such as cylinders. The sum of these volumes would closely estimate the capacity of the whole body. The smaller the slices were made, the more accurate the resulting measurement would be. Those familiar with integral calculus will know that this is the conceptual foundation for this branch of mathematics, which was conceived years later.

Additionally, Kepler sought to determine the barrel shape that would maximize the volume of wine inside. With that goal in mind, he created a rudimentary form of differential calculus, which is used for problems involving optimization such as this. (These contributions to differential calculus were also largely uncredited, as Pierre de Fermat would receive the primary recognition later in the century.)

With these new techniques, he discovered that—much to his surprise—the barrel he'd received and the rod method used to measure its volume were actually fairly close to being mathematically sound. The shape of a standard Austrian wine barrel, like the one he originally purchased, was reasonably maximized for volume, and enabled accurate measurement when the technique the merchant employed was used—even when the overall size of the barrel changed.

Kepler concludes Nova Stereometria Doliorum Vinariorum with his attempts to determine the volume of a partially empty wine barrel—a problem for which he did not come up with any solutions.

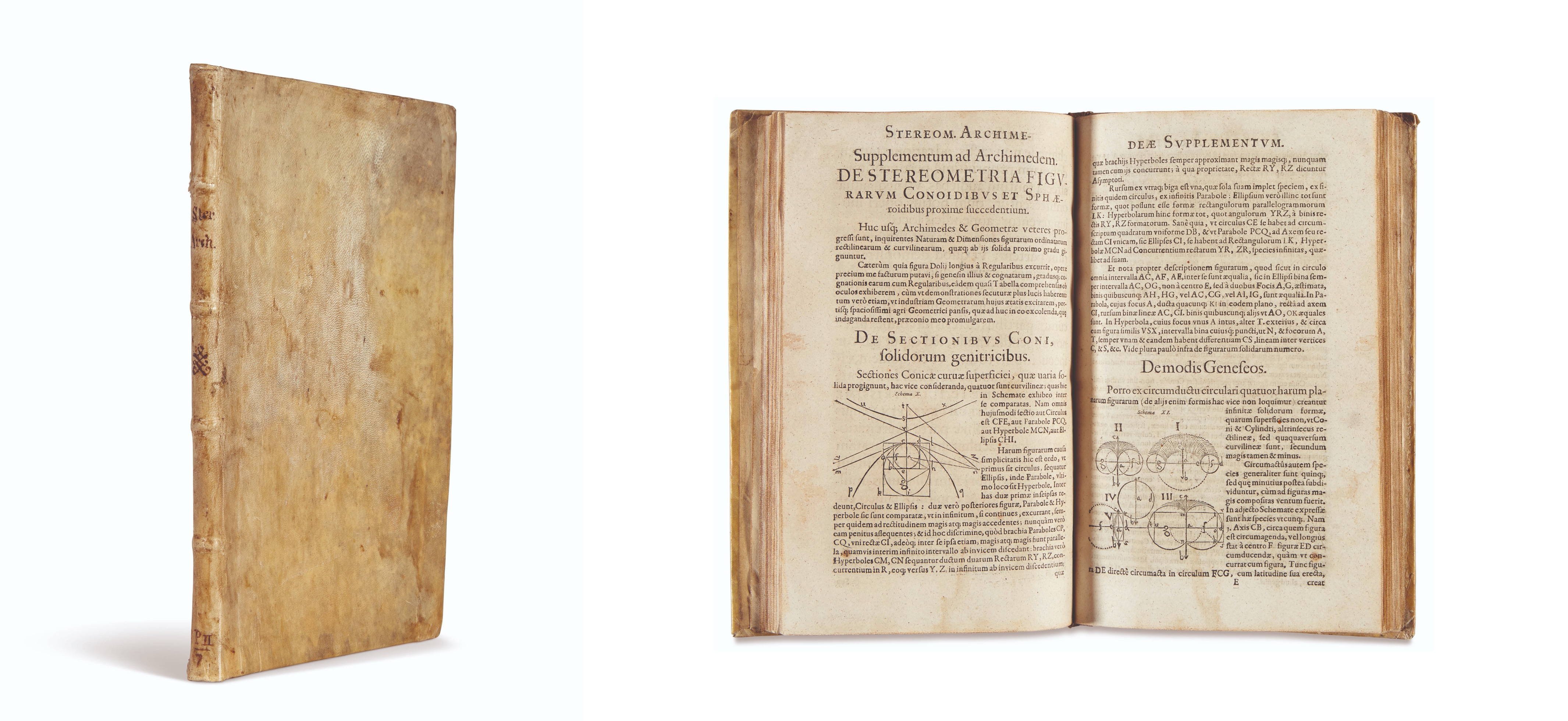

Copy of Nova Stereometria Doliorum Vinariorum, First Edition, sold at auction 2019 | Christie’s

While it may not have advanced wine barrel design, mathematical historians count Nova Stereometria Doliorum Vinariorum as a significant contribution to the development of calculus. But historians aren’t the only ones who value it; first-edition printings of the book, produced in Linz, Austria in the early 17th century, are also worth quite a bit to collectors. They occasionally come up for sale and often fetch a significant value, like this copy that was sold at auction at Christie's in 2019 for a closing price of $32,500 USD, roughly double the estimated sale price.

Now, what might Kepler have been getting delivered? There isn't any record of what wine he ordered, but during this period in the early 17th century, the most popular ones in Europe were sweet wines like Riesling, Sauternes, and Hungarian Tokaji, as well as fortified wines like Port, Madeira, and Sherry. Austria was also producing its own wines at this time, with records indicating that Grüner Veltliner—Austria's most-grown variety today—has been cultivated there since before the time of the Roman Empire. For delivery, most, if not all, wine was purchased and served by the barrel, much like the one Kepler received. Glass bottles were not yet widely used for the shipping, storing, or aging of wine.

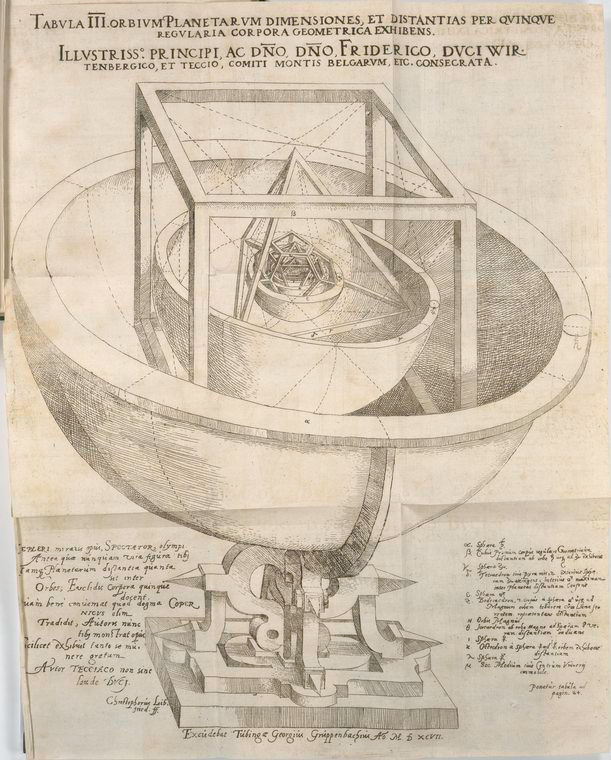

Device illustrated in Mysterium Cosmographicum

It's worth noting that this isn't the only alcohol-related contribution that Kepler made to science. A few years before he developed the concepts for and wrote Nova Stereometria Doliorum Vinariorum, Kepler published Mysterium Cosmographicum, highlighting his early astronomical theories on planetary motion. These ideas supported Nicolaus Copernicus's heliocentric model (postulating that planets revolve around the sun) and speculated on the size and shape of our solar system's orbits. To present his hypotheses, he designed and drew the illustration of the device pictured above in Mysterium Cosmographicum, which would display the geometric movements of the planets known at the time.

Historians believe that Kepler intended to physically craft this device from silver, with each of the individual shapes as a liquor-holding vessel. Each would hold a different beverage, and, presumably, partygoers would be able to dispense their desired liquor from a tap connected to the orbital container of their choice.

Though this model for describing paths around the sun turned out to be incorrect, his work here directly led him to create the laws of planetary motion for which he is most famous. Isaac Newton later proved the accuracy of those laws as a close approximation for the trajectories of the planets within our solar system.

While Kepler’s tipple-fueled contributions to science, astronomy, and mathematics are undoubtedly laudable, it’s probably a good thing that today’s scientists and astronomers aren’t so closely tying alcohol to their work.